Efficient Production of Busbars for Faster Charging of Electric Cars

Weld seams produced with Electromagnetic Pulse Technology (EMPT) are very stable and helium-tight; i.e. no corrosive medium can penetrate.

Posted: July 18, 2024

Electric cars should charge safely and quickly, and the electrical installations should be light and compact. Busbars offer these advantages over conventional cables, and with electromagnetic pulse technology (EMPT), a cost-effective manufacturing method suitable for large-scale production is also available.

The driver of an electric vehicle not only demands an acceptable range from his vehicle, but it should also be quick to charge. This is why car manufacturers prefer to work with 1000 A if possible. The cables heat up in the process and they are also heavy and bulky. Here, busbars offer significant advantages.

Unlike a cable, a busbar always has its tested short-circuit resistance. Changing the direction of cables sometimes requires large bending radii. Busbars, on the other hand, can be bent with small radii. Furthermore, cables have to be laid at a distance due to the possible lost heat. With busbars, this is not necessary, and their use significantly reduces the space required. And very importantly: Busbars do not burn. Furthermore, installing busbars only takes about one third of the time compared of installing cables, and in the case of a power distribution system, it is even 70 percent faster, as the rigid busbars are easier to automatically install than the flexible cables.

Busbars also offer long-term reliability in harsh environments and can withstand operating temperatures from -40 to +125 °C. They can dissipate heat and thus help to prevent overheating. Thanks to lower inductance and higher capacitance compared to cables, they make charging more efficient.

Efficiently Joining Aluminum and Copper with EMPT

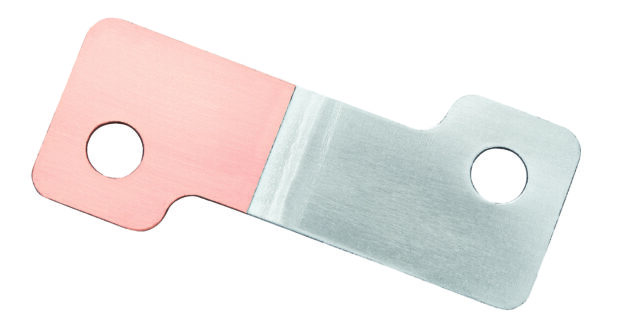

The most suitable materials for busbars are aluminum and copper. For cost reasons, the majority of the busbars should be made of inexpensive aluminum, but the expensive copper is needed for the contacts. However, when the two metals and condensation water come together, a violent electrochemical reaction starts. The copper corrodes the less noble aluminum, contact resistance and temperature rise, and in the worst case, a fire can occur. In addition, the two metals are not easy to join.

“Here is where the EMPT technology comes into play. It works quickly, can be easily automated and is safe. The weld seams produced with it are very stable and helium-tight; i.e. no corrosive medium can penetrate. The restrictions regarding the geometries of the parts to be joined are less stringent than with other processes,” summarized Dr. Ralph Schäfer, Head of Research and Development at PSTproducts.

The main components of such an EMPT system are the pulse generator, control cabinet, and, depending on the application, flat coils or field shapers. A pulse generator consisting of capacitors connected in parallel supplies the currents required to generate the magnetic field. When the high-current switch is closed between the coil and the capacitors, the current flows into the coil in pulses. Pulsed currents in the range of several 100 kA to over 1.000 kA can be generated. With coils and field shapers, the magnetic pressure is directed towards electrically conductive workpieces. The coil consists of one or more electrical windings and is usually made of a high-strength copper or aluminum alloy. The cross-section of the coil is usually between 10 mm2 and several 100 mm2. The required power supply capacity is limited to 380V/64A even for powerful systems due to the 3 to 8 seconds it takes to charge the capacitors. The power consumption ranges from 0.015 to 0.03 kWh per pulse, depending on the size of the system.

EMPT welding is based on an electromagnetic pulse, shorter than 100 µs. The pulsed current has a very high amplitude and frequency, typically several 100 kA and discharge frequencies between 10 and 50 kHz, and thus creating a strong magnetic field that generates an eddy current in one of the workpieces. The two workpieces are positioned overlapping, with an acceleration gap in between. The coil accelerates one of the two workpieces towards the joining member. When this workpiece area impacts its contact partner, repulsive Lorentz forces and a high magnetic pressure are generated, which exceed the yield strength of the material and allow the workpiece to impact a stationary joining member at speeds at up to 500 m/s. In the collision area, extremely high mechanical stresses and strains occur.

The maximum voltage occurs at the contact point and creates a kind of bow wave in front of the joining area of the two workpieces. This plastic deformation breaks the superficial oxide layers of both contact partners and leaves behind a wavy structure. The air gap between the workpieces is compressed and blows dirt and chipped oxide particles out of the joining area.

The two surfaces are pressed together under enormous pressure, causing the atoms of the joining members to form a metallic bond. As the melting point of the joining partners is not reached, metals with different melting points can be joined without warping. The joining area typically has a higher strength than the weaker base material. EMPT welding works without an increase in temperature and therefore without any changing the microstructure, i.e. without a weakening heat-affected zone.

Another major advantage is that the transition resistance is not increased during EMPT welding of aluminum and copper, and the good conductivity of both metal partners remains intact across the joint. Additionally, the joint has significantly better final resistance values to thermal shock and vibration according to common test procedures than resistance or laser welding.

EMPT welding produces high-quality weld seams without the use of shielding gases or welding additives. Pulse generators and coils from PSTproducts have now been optimized to the point that a service life of over two million pulses can be easily achieved before capacitors or parts of the coil need to be replaced.

EMPT welding has been used by international customers for many years to manufacture components in large series quantities. A plant typically performs 1 to 5 million welds per year. In addition, the process is environmentally friendly, as neither smoke nor radiation are produced. The magnetic field and thus the welding parameters can be controlled very precisely, thus providing a constant, documentable quality.

With an EMPT system, up to ten busbar joints can be performed per pulse with cycle times of five seconds or more. This makes this welding process commercially cost-efficient. This allows that mass production in the tens of millions of units per month can be produced with material thickness of up to 4 mm. Up to 8 mm material thickness is currently technologically possible.

EMPT Welding Suitable for Large-scale Production

“PSTproducts has extended the life expectancy of pulse generators and coils by choosing suitable materials and optimizing manufacturing equipment, thus increasing maintenance intervals to 500,000 to 2,000,000 impulses. The joining costs could thus be reduced to just a few cents. The availability of EMPT machines meets today’s industrial requirements with 100% process control and proven use in fully automated production lines,” Schäfer reported.

Such busbars are a topic wherever large currents are transmitted, not only in vehicles, but also in wind power and electric ship propulsion systems.

PSTproducts offers interested parties a detailed analysis, prototype and initial sample production and also a pre-series for every application, if the customer so wishes. The team provides advice on plant construction, later on conversion, upgrading and/or modernization of existing plants.

Busbars will replace a part of the wiring in e-mobility for the near future, thus making it safer. And they also offer major advantages for photovoltaic and wind power systems. And with EMPT welding, one has a reliable process that can also join future materials, with only one restriction: the materials must be electrically conductive.