Beat the Competition on a Budget with this Entry-Level ‘Automation’

The way we machine parts has changed significantly over the years. Now it’s time to change how we think about workholding too.

Posted: February 2, 2016

Automation is a like a train coming down the tracks. The global players have had it in their factories in one form or another for years, some for decades. And now, with the proliferation of ideas like the Internet of Things, Big Data, the Cloud and the practice of Smart Manufacturing, faster, unattended operations are more accessible than ever. As all of this inevitably creeps more and more on to the metalworking floor, shops that don’t keep up will struggle to compete. But I come to you with a less drastic, less expensive alternative that accomplishes a lot of the same things that robots and machine tools that “talk” do. It comes in the form of a workholding solution. That’s right. I said workholding.

Historically, different types of machine tools were delivered with a unique workholding interface. Surface grinders typically came with a magnetic table; lathes received three-jaw or four-jaw chucks or collet systems; milling machines are still based on a T-slot table. But these days, milling, turning and some grinding can be performed in a single machine or several machines grouped in a cell. The way we machine parts has changed significantly over the years . . . it’s time that we change how we think about workholding too. Workholding shouldn’t be considered as just an obstacle between cycles. You don’t need to believe that it requires a well-coordinated “NASCAR pit crew” (as I once read in another article) to swap setups. And we need to stop thinking that workholding devices can’t add value because they don’t remove material.

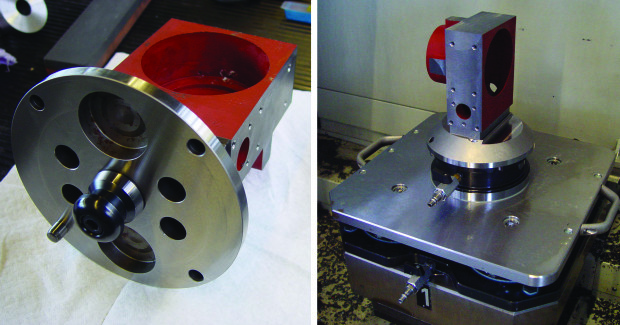

Quick, accurate and stable gripping can easily be accomplished, regardless of the workholding form, when the fixture workpiece is transferred in and out of the machine tool with something like a Unilock zero-point clamping system. In fact, systems like this provide the best solution to two of manufacturing’s toughest setup problems: repeatability of location from one fixture or workpiece blank to another, and transfer of work from one machine tool to another (more on that in a minute). These kinds of systems aren’t new, but they’ve grown right alongside advancing approaches to machining and can now adapt to workpieces of virtually any shape or size.

For some perspective, when the Unilock zero-point clamping system was introduced over 20 years ago, eight choices for receivers were offered with varying footprints to address workpiece size and required rigidity. Six standard retention and positioning elements were also offered. Now there are over 45 receivers and 60 retention and positioning elements, many of which have been designed specifically to streamline the implementation process. Unilock uses air pressure plus die springs to drive clamping pins against a tapered clamping knob that is attached to a base plate, fixture or directly to the workpiece for easy palletization of single or multi-chuck applications. Simply transfer air pressure to the opposite side of the chuck to hold it open for changeover. In the case of Unilock, the addition of air pressure provides from 660 lb to 8,800 lb of clamping force while achieving repeatability of 0.0002 in or better.

With this kind of system arrangement, a workpiece reference location need only be established once. Alignments for the chuck are established from its center line, and that data can be captured electronically and kept in the machine’s CNC program. Work can then be moved from turning center to a grinder or from a machining center to a CMM without having to re-establish the reference point. You can run any fixture at any time. If you don’t believe a workholding device can directly improve throughput, think again. A clamping system gives a creative machinist a chance to shine by finding ways to machine a part through the second and third steps without ever unclamping the part. Not only is this a faster way of doing things, but feature-to-feature accuracy is improved, it reduces the chances of human error, and the operator doesn’t have to judge how much time is required to take the part out.

Converting a single machine tool or cell over does take time and money; when a shop is busy, it is difficult to pull a machine out of production for the implementation of process improvements. But there is an immediate return and the conversion process for the machine table is a lot like a setup change, and a skilled machinist can accomplish it quickly. If you make the transition, more time and effort will be dedicated to converting workholding components that need to be loaded into a quick change receiver by adding positioning and clamping elements.

The biggest single differentiator in production cost between shops is labor. It’s likely that 90 percent of the jobs you lost out on are because the other shop (especially if it’s in low-wage Mexico or Asia) managed to beat you on the labor. The fact is, every time somebody touches the part, it costs money. I believe palletizing an entire production can remove at least 75 percent of handling time; plus, once you get to the point of automated production, the common workholding interface will reduce implementation costs. These are reasons why I think of the right workholding as a form of entry-level automation – the kind of affordable automation that can keep competitors with expensive robots, clouds and software at bay. As for those who aren’t onboard the automation train, you’ll whoop them on the labor line of your estimate every time.

Once again: It’s time to change the thinking about workholding.