Rethinking Power Transmission

A new grid is being assembled to transmit power as well as information through the air, without wires. Chris Mims of WSJ examines how this could unlock an age of wonders.

Posted: October 30, 2015

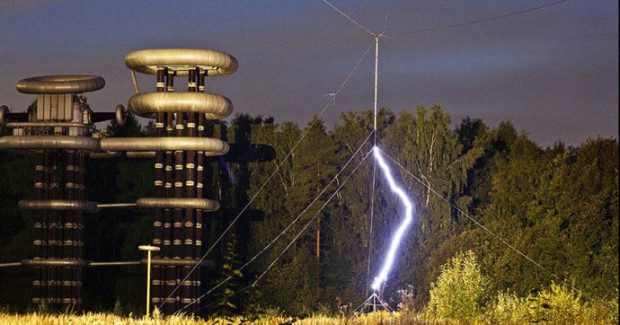

In 1902 workers completed a mysterious tower, 187 ft high and shaped like a giant mushroom, on which rested the hopes of one of the 20th century’s most prolific geniuses. Facing the beach in the hamlet of Shoreham, NY, on Long Island, the Wardenclyffe Tower was, according to its inventor, Nikola Tesla, the key that could unlock an age of wonders.

As Tesla later wrote, the tower’s ability to transmit information to the far side of the Earth would someday allow the creation of “an inexpensive instrument, not bigger than a watch, [which] will enable its bearer to hear anywhere, on sea or land, music or song however distant.” Sometime in 2016, Tesla’s other prediction — that it isn’t only possible, but commercially viable, to transmit power as well as information through the air, without wires — is expected to come true.

What is coming are hermetically sealed smartphones and other gadgets that charge without ever plugging into a wall. And soon after there will be sensors, cameras and controllers that can be stuck to any surface, indoors or out, without the need to consider how to connect them to power. Wireless power will be, in other words, not just a convenience, but a fundamental enabler of whole new platforms.

The players in this field are myriad, but their technology can be boiled down to four basic types. There are those power mats you may have seen at Starbucks, an older technology that hasn’t been widely adopted. The second, pioneered by the 8-year-old company WiTricity Corporation (Watertown, MA), is slated to show up in Intel-chip-powered laptops sometime in 2016. It uses “magnetic resonance” to efficiently transmit power, over distances ranging from centimeters to a meter. “It’s really charging that Intel notebook as if you’d plugged it in,” says WiTricity chief executive Alex Gruzen.

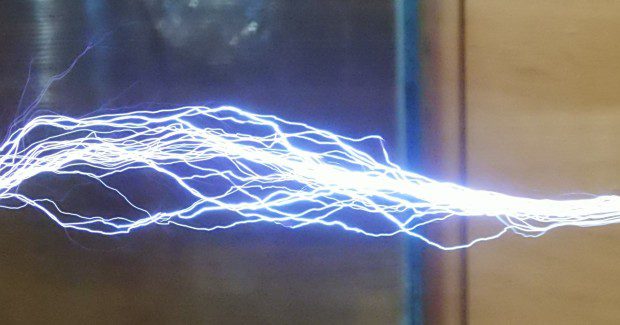

But it is the third and fourth kinds of wireless power that are the most intriguing, because they involve beaming power over significant distances. One, which the startups Energous Corporation (San Jose, CA) and Ossia Inc. (Bellevue, WA) are racing to commercialize, involves transmitting power more or less as Tesla envisioned — through radio waves. And the last, pioneered by uBeam (Santa Monica, CA), involves transmitting power through sound waves.

The challenge with these approaches isn’t technology, but physics. Radio waves, after all, are in the same range as the waves generated by a microwave oven. There’s only so much energy you can beam through the air without cooking whatever gets in the way. Energous chief executive officer Michael Leabman claims his two-year-old company has this problem licked, and not because of breakthroughs in focusing radio waves. The key, experts say, is that mobile devices use less power than ever.

“It’s really the chip makers who deserve most of the credit for this stuff,” says Gregory Durgin, a Georgia Institute of Technology professor who is an expert on wireless transmission of power. He says the claims that Energous is making for its technology are in line with his own experience. A typical smartphone might be able to charge quickly from a wall outlet putting out 5 watts, but if you can — as Energous claims — beam up to 2 watts of power over a distance of 10 ft to a small radio antenna embedded in that phone, you can “trickle charge” it in a matter of hours.

If you think about how much time we typically spend in our offices and homes, this is a perfectly reasonable way to almost guarantee that we’ll never have a dead phone again, especially if our devices start charging automatically the moment we walk in the door. Energous has shown off a workable demo, and Leabman says the company’s technology will be a mass-market product by the end of 2016 or early 2017.

Just as exciting is the potential of wireless energy to solve the problem that has always plagued the Internet of things — or the idea that we will cover our entire world in sensors and tiny motors that control devices, leading to “smart” everything. The hitch is, how to power all those little chips and their electronics, some of which may be as small and thin as a stick-on price tag.

Energous already has a patent on the idea of putting a power transmitter into the base of a light bulb, allowing its technology to cover an entire room, and putting out enough power that a device 15 ft away could absorb one watt. “Wireless power could enable a whole new class of devices,” says Durgin. Those devices will include sensors on all the mechanics of a home, business or factory; detectors for heat, light and motion; and cameras and controls that we can move and upgrade at our convenience, without ever having to touch the building’s wiring. These controls will include “peel and stick” light switches and thermostats, which are already a common senior design project among Professor Durgin’s students.

Meredith Perry, the chief executive officer of uBeam, says that her company’s technology will be able to beam more power, via ultrasound waves, over greater distances than what is claimed by companies like Energous, and that uBeam will unveil a working prototype by the end of 2016.

Both of these technologies face major issues. In the case of uBeam, experts I spoke with were skeptical that, based on the physics involved, the company can deliver on its promises. Moreover, energy transmitted via radio waves represents a major pollution of the bands of unregulated spectrum that already are crowded with everything from microwave ovens to Wi-Fi routers. That could limit the places wireless power can be used. So it isn’t likely that the three-prong outlet will be obsolete anytime soon, but it is likely that in the near future ambient power could be commonplace.

It would be the ultimate vindication of Tesla, a hundred years after his tower project was shut down for lack of funds.

This article is taken from the October 2, 2015 issue of The Wall Street Journal. Christopher Mims is a technology columnist at WSJ. Previously, he was a science and technology correspondent and editor for Quartz, and been an editor at Scientific American, Technology Review, Smithsonian and Grist. He can be reached at [email protected].