The Injury Continuum

When a worker screws up and gets hurt, organizations tend to react in one of two ways: Either they rush head long to the conclusion that the errant employee needs more training or they are resolute in the belief that the worker knew (or should have known) that what he or she did was wrong and did it anyway. While these circumstances are sometimes the case, they are far from the only possibility.

Posted: March 4, 2014

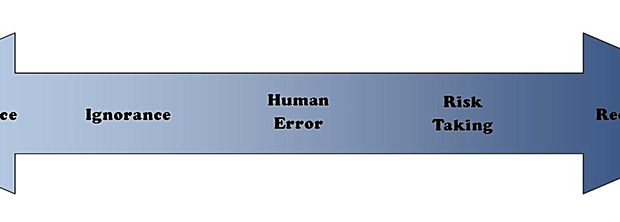

When it comes to worker injuries there is an entire continuum of possibilities. On one end of this continuum is incompetence — the worker (or the equipment) is incapable of working safely. At the other end of the continuum lies recklessness; the wanton disregard for the safety of oneself or others. In between these extreme lies a host of conditions that are equally capable of injuring (or even killing) workers. In keeping with my penchant for pretention, I’ve dubbed this La Duke’s Continuum (see Figure 1).

INCOMPETENCE

Incompetence is a leading cause of organizational problems. There are three areas of incompetence of which organizations should be aware:

- Operational incompetence occurs when the organization expects equipment to perform at a more reliable rate than it is capable; simply stated, the organization has the wrong equipment to adequately do the job. Many companies that are struggling to recover from the global recession are facing operational incompetence as facility and maintenance budgets, cut to the bone, are no longer able to keep machines and facilities in optimum condition.

- Procedural incompetence tends to grow out of static policies employed in a dynamic business environment. Organizations that don’t periodically review and proactively change policies to keep up with the times ultimately find themselves with procedures and policies that no longer make sense. These vestigial practices lead to a state of procedural incompetence.

- Personal incompetence. Many organizations hire and retain workers that cannot mentally, physically, or emotionally do the job; these organizations have the wrong people doing the jobs and this personal incompetence puts workers at risk. Sometimes companies worry that requiring a policy that workers demonstrate the physical ability to do the job might somehow violate discrimination laws, but this can be avoided by conducting post-offer testing.

Whether an organization has the wrong equipment, the wrong rules, or the wrong people the environment in which it operates is a failure waiting to happen. Unfortunately, despite the real dangers of incompetence at an organizational level, many organizations turn a blind eye to opportunities to make real improvements in this area. Sometimes failures are caused by drift — the unintentional movement from the standard.

Drift occurs as variability in human behavior (or even mechanical degradation — equipment wears out over time) takes the worker farther and farther away from the process as designed. Pretty soon the worker is engaged in activities that the process engineers and designers never imagined and the result can be catastrophic.

IGNORANCE

Just as the recession has hobbled maintenance and facilities by slashing budgets, the skill level of many workers has diminished as training budgets are slashed. Too often organizations judge the value of training in terms of volume — a lot of training is seen as automatically better than a little training. In many cases, doing less training, but concentrating on a relatively few core skills, is far more effective than a blitz of largely ineffectual training courses. All things being equal, organizations that focus their efforts on training workers to a mastery level of their core job responsibilities will tend to have safer workplaces. When it comes to training, sometimes less is more.

HUMAN ERROR

Sometimes people just mess up; they don’t mean to, but it just happens. There is little we can do to prevent workers from committing errors (yes, we can help them manage performance inhibitors that make errors more likely — for example, lack of sleep, reporting to work unfit for duty after a night of hard partying, or similar conditions — but even here there are limits to what we can do. The bottom line is that while everyone makes mistakes, nobody should have to die because of one.

Operations where a simple error can mean the difference between life and death should focus on preventing the injury caused by the mistake instead of wasting time trying to reengineer the human brain. At very least the organization should look for ways to reduce the severity of the most likely injuries caused by human error. Many still believe that human error can be eliminated using rudimentary behavioral modification techniques. Such techniques often fail to address the considerable variability of human behavior and end up lulling organizations into a false sense of security.

RISK TAKING

Risk taking is necessary for life. Workers can’t get out of bed, shower and dress, and commute to work without assuming a certain amount of risk. Risk taking becomes problematic, even dangerous, when workers take uncalculated or poorly calculated risks. Organizations need to help workers to understand the risks that the workers are taking, the probability of failure, and the likely consequences if things turn out badly. Organizations should also closely monitor its risk tolerance (the level of risk that workers will deem to be acceptable) as, like drift, risk tolerance increases so gradually that it can go unnoticed until it crosses a threshold and tragedy strikes.

RECKLESSNESS

Sometimes a worker’s risk taking exceeds any justification; the potential reward is so entirely out of proportion with the dangers of an action that a reasonable person would judge it to be unacceptable. Recklessness is relatively rare occurrence, but it’s out there; workers get frustrated, suffer from impaired judgment, or for some other reason lash out. In these cases the workers know, or should know, better to behave in this way but they do it anyway. Recklessness should be dealt with under the organization’s disciplinary policy.

Worker injuries are serious and emotionally charged events that make it easy for organizations to succumb to the temptation to overly simplify the cause. In fact, the temptation can be so great that organizations routinely devolve into a binary state and default to either training or discipline when the true cause lies somewhere else along the continuum.