Why Can’t I Stick Weld with My MIG Machine?

An explanation of the difference between Constant Current and Constant Voltage Output.

Posted: November 7, 2013

Q: I have a small MIG welder at home. I want to use it for some stick welding, but I have been told I cannot. Why is this? At work we have several different types of welding machines. Why is it that some only can be used for stick welding and some only for wire welding, but there are other machines that can be used for both? I have heard the terms CC and CV, but what do these mean and why are they important? Finally, our company has some suitcase wire feeders with a “CV / CC” switch inside of them. Does this mean they can be used with any welding machine?

A: These are excellent questions and ones I am sure have been asked by many welders. From a design and arc control standpoint, there are two fundamentally different types of welding power sources. These include power sources that produce a constant current (CC) output and power sources that produce a constant voltage (CV) output. Multi-process power sources are those that contain additional circuitry and components that allow them to produce both CC and CV output, depending on the selected mode.

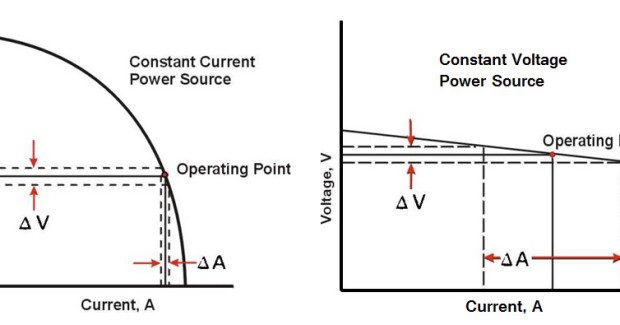

Note that a welding arc is dynamic, in which current (A) and voltage (V) are changing constantly. The power source is monitoring the arc and making millisecond changes in order to maintain a stable arc condition. The term “constant” is relative. A CC power source will maintain current at a relatively constant level, regardless of fairly large changes in voltage, while a CV power source will maintain voltage at a relatively constant level, regardless of fairly large changes in current.

Figure 1 contains graphs of the typical output curves of CC and CV power sources. Notice at various operating points on the output curve in each graph how there is relatively little change in one variable, while fairly large changes in the other variable (“Δ” (delta) = difference).

It should also be noted that this article only covers conventional types of welding power sources. When pulse welding with many of the newer Waveform Control Technology power sources, you really cannot consider the output to be strictly CC or CV. Rather, the power sources are monitoring and changing both voltage and current at extremely fast rates (much faster than conventional technology power sources), in order to produce very stable arc welding conditions.

Before discussing the question of CC vs. CV, we must first understand the effects of both current and voltage with arc welding. Current effects the melt-off rate or consumption rate of the electrode, whether it be a stick electrode or wire electrode. The higher the current level, the faster the electrode melts or the higher the melt-off rate, measured in pounds per hour (lbs/hr) or kilograms per hour (kg/hr). The lower the current, the lower the electrode’s melt-off rate becomes.

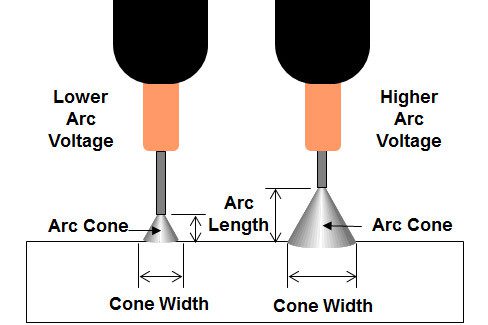

Voltage controls the length of the welding arc, and resulting width and volume of the arc cone. As voltage increases, the arc length gets longer (and arc cone broader), while as it decreases, the arc length gets shorter (and arc cone narrower). Figure 2 illustrates the effect of voltage in the arc.

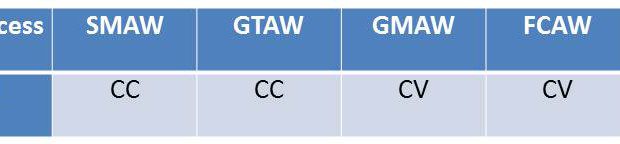

The welding process you are using, and its associated level of automation, determines which type of welding output is most stable and thus preferred. The Shielded Metal Arc Welding (SMAW; aka MMAW or stick) process and the Gas Tungsten Arc Welding (GTAW; aka TIG) process are both generally considered manual processes. This means you control all welding variables by hand. You hold the electrode holder or TIG torch in your hand and control travel angle, work angle, travel speed, arc length and the rate in which the electrode is fed into the joint all by hand. With the SMAW and GTAW processes (i.e., the manual processes), CC is the preferred type of output from the power source.

Conversely, the Gas Metal Arc Welding (GMAW; aka MIG) process and the Flux Cored Arc Welding (FCAW; aka flux core) process are both generally considered semi-automatic processes. This means that you still hold the welding gun in your hand and control travel angle, work angle, travel speed and contact tip-to-work distance (CTWD) by hand.

However, the rate in which the electrode is fed into the joint, known as wire-feed speed (WFS), is controlled automatically with a constant-speed wire feeder. With the GMAW and FCAW processes (i.e., the semi-automatic processes), CV is the preferred output.

Table 1 contains a summary of the recommended output types by welding process.

For a simpler design and to keep purchasing costs low, welding power sources are generally designed to be used with just one or two types of welding processes. To this end, a basic stick machine will have CC output only, as it is intended for stick welding only. A TIG machine also will have CC output only, as it is intended only for TIG and stick welding. Conversely, a basic MIG machine will have CV output only, as it is intended for only MIG and flux core welding.

Regarding your first question, “Why can’t I stick weld with my MIG machine”, the answer is because your MIG machine only has CV output, which is not intended or recommended for stick welding. Conversely, you generally cannot MIG weld with a stick machine with CC output, because it is the wrong type of output for MIG welding.

As mentioned earlier, there are multi-process welding power sources that can produce both CC and CV output. However, they are generally more complicated, have higher output capability, intended for industrial applications and not priced at a basic, entry level welding machine cost range. Figure 3 shows examples of typical CC, CV and multi-process welding machines.

You can create a welding arc with any of the welding processes on either CC or CV type of output (if you could configure the welding equipment to do so). However, when you use the preferred type of output for each respective process, the arc conditions are very stable. However, when you use the wrong type of output with each respective process, the arc conditions can be very unstable. In most cases, they are so unstable that it makes trying to maintain an arc impracticable.

Now let’s discuss why these last statements are true. With the two manual processes, SMAW and GTAW, you are controlling all variables by hand (which is why they are the two most operator skill intensive processes). You need to have the electrode melt at a consistent rate, so that you can feed it into the joint at a consistent rate. To do this, the welding output needs to maintain current at a constant level (i.e., CC), so that the resulting melt-off rate is consistent. Voltage is a less controlling variable.

With manual processes, it is very difficult to consistently maintain the same arc length because you are also constantly feeding the electrode into the joint. Voltage varies as a result of changes in arc length. With CC output, current is your preset, controlling variable and voltage is simply measured (typically as an average value) while welding.

If you tried to weld with the SMAW process, for example, using CV output and current, the resulting melt-off rate would vary too much. As you were traveling along the joint (trying to be consistent with all other welding variables), the electrode would melt at a faster rate, then a slower rate, then a faster rate, etc. You would constantly need to change the rate in which you fed the electrode into the joint. This is an impracticable condition, thus making CV output undesirable.

When you switch to a semi-automatic process, such as GMAW or FCAW, something changes. While you are still controlling many of the welding variables by hand, the electrode is being fed into the joint at a constant speed (based on the particular WFS you have set on the wire feeder). Now you want the arc length to be consistent. To do this, the welding output needs to maintain voltage at a constant level (i.e., CV), so that the resulting arc length is consistent.

Current is a less controlling variable. It is proportional to, or a result of, the WFS. As WFS increases, so does current and vice versa. With CV output, voltage and WFS are your preset, controlling variables and current is simply measured while welding.

If you tried to weld with the GMAW or FCAW processes using CC output, voltage, and the resulting arc length, would vary too much. As voltage decreased, arc length would become very short and the electrode would stub into the plate. Then, as voltage increased, arc length would become very long and the electrode would burn back towards the contact tip. The electrode would be constantly stubbing into the plate, then burning back towards the tip, then stubbing into the plate, etc. This is an impracticable condition, thus making CC output undesirable.

As a side note, it is also common to fully automate the GTAW, GMAW and FCAW welding processes. In the case of full automation, all variables are controlled by a machine and held at a constant angle, distance or rate. Therefore there is less change in the arc conditions. However, the preferred output type for automated GTAW is still CC, while CV is preferred for automated GMAW and FCAW.

The fifth common arc welding process, Submerged Arc Welding (SAW; aka sub-arc), is typically an automated process, as well. With SAW, either CC or CV output is commonly used. The determining factors as to which output type is best are generally electrode diameter, travel speed and size of weld puddle. With semi-automatic SAW, CV is the preferred type of output.

Your last question was about suitcase-style wire feeders (see example in Figure 4). This is a piece of equipment that allows you go against the basic rules just covered in this article . . . to an extent. They are designed primarily for field welding applications and have three unique features compared to conventional shop style wire feeders.

One, the wire is enclosed inside a hard plastic case for better protection and durability in the field. Two, they do not require a control cable to power the drive motor, but rather use a voltage sensing lead from the wire feeder. So hook-up is simple, just requiring the use of the power source’s existing welding cable (and the addition of a gas hose). Three, they do have the ability to operate with a CC power source, but with LIMITED success. They do have a “CC/CV” toggle switch in which you select the type of output from the power source.

When these suitcase-style wire feeders first came out, the theory was that they could be used with a large existing base of CC power sources already in the field (most primarily, engine-driven welders) and thus now give fabricators GMAW and FCAW (i.e., wire welding) capability. Instead of having to buy a brand new CV power source, they only needed to get the wire feeder.

To compensate for the fluctuations in voltage which occur with CC output, these wire feeders have extra circuitry that slows the wire-feed speed response to changes in voltage, in an attempt to help stabilize the arc. Note that on CC, wire-feed speed is no longer constant, but rather it continually increases and decreases in an attempt to keep current at a constant output).

The reality of wire welding with CC output is that it works fairly well with some applications and poorly with others. There is relatively good arc stability with the gas-shielded flux cored (FCAW-G) process and the GMAW process when in a spray arc or pulse spray arc mode of metal transfer. However, arc stability is still very erratic and unacceptable with the self-shielded flux cored (FCAW-S) and the GMAW process when in a short circuit transfer mode of metal transfer.

While voltage varies with CC output, processes that generally operate at higher voltages (i.e., 24V or more), such as FCAW-G and spray arc or pulse spray arc MIG, are less sensitive to the voltage variations experienced with CC output. Therefore arc stability is pretty good. Whereas processes, such as short circuit MIG and FCAW-S, which generally operate at lower voltage settings (i.e., 22V or less), are more sensitive to voltage variations. Therefore arc stability is much worse and generally considered unacceptable.

Another factor with FCAW-S electrodes on CC output is that excessive arc voltages and resulting longer arc lengths can in essence over expose the arc to the atmosphere. This can potentially result in weld porosity and/or a sharp decrease in the weld metal’s low temperature impact toughness.

As a final note, CV output is ALWAYS recommended for wire welding. Therefore, when using these suitcase-style wire feeders with a power source that has CV output capability, use it instead of the CC output. Finally, while CC output can be acceptable for general purpose FCAW-G and spray-arc and pulse spray-arc MIG welding, it is not recommended for code quality work.

Subscribe to learn the latest in manufacturing.